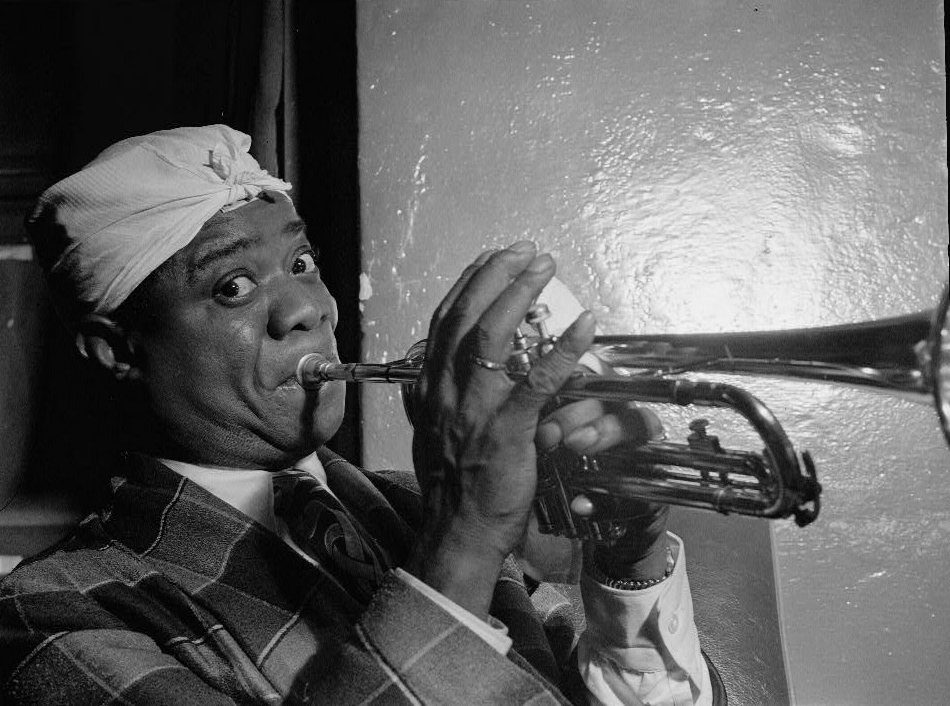

Anniversaries abound in the coming days. The New Yorker reminds us that on August 11 it will have been 50 years since a drunk Jackson Pollock crashed his Oldsmobile into a tree, killing himself and a passenger. [One is tempted to be a smartass here and offer up “In My Merry Oldsmobile," a 1927 foxtrot capably rendered by Jean Goldkette & His Orchestra and featuring Bix Beiderbecke, about whom more in a moment. –Ed.] Marking such an event is “dismal enough,” writes Peter Schjeldahl, but, he admits, it’s also “glamorous, in its way. Pollock, like other doomed artists and martyrs to fame in his era—Charlie Parker and Billie Holiday, Marilyn Monroe and James Dean—advanced and, by destroying himself, oddly consecrated America’s postwar cultural ascendancy. Sometimes a new, renegade sensibility really takes hold only when somebody is seen to have died for it.”*

Handy Axiom: It is easiest to find a death glamorous, not to mention sacred, when you are not the one doing the dying.

And speaking of the “doomed,” this coming Sunday marks the day, 75 years ago, when Bix Beiderbecke died a pathetic, gin-soaked death in a Queens boarding house. Like the commemoration of Pollock’s death,** it’s an occasion that could well be described as “dismal enough” were it not for the fact that it will also mark my second wedding anniversary. No, Kate & I did not choose August 6 out of some morbid tribute to Bix, although he did happen to figure briefly in our courtship. I described the moment in an essay last year:

Bix is a mystery. Bix is “a riddle wrapped in an enigma,” according to the website of the Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Society. And in the smoky shadows of a bar in downtown Bangor, Maine, Bix is a pickup line. This is where, on a particularly cold January evening, I met my future wife. I immediately angled the conversation to music, and when she professed a love for jazz, I smugly tested her on whether she’d heard of Bix Beiderbecke.

“You’re from Davenport?” she exclaimed a few moments later, touching her hand on my arm. “That’s so cool!”

Bix, it should be said, is not only a mystery. He is a “blamming, slamming, fun-cramming party,” according to Quad-City Times columnist Bill Wundram on the occasion of last weekend’s Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Jazz Festival in Bix’s hometown of Davenport, Iowa. “Bix is a trance,” said Wundram. He’s also “emotion and love,” “courage,” and “being happy.”

Bix is memories, of guys like the late Les Swanson, who would tap his cane to the jazz and munch a cheese sandwich alongside the levee bandshell. He knew Bix well; played piano alongside him; and always grumbled at the weekend Beiderbecke hoopla: “Bix would just raise his hands in horror.”

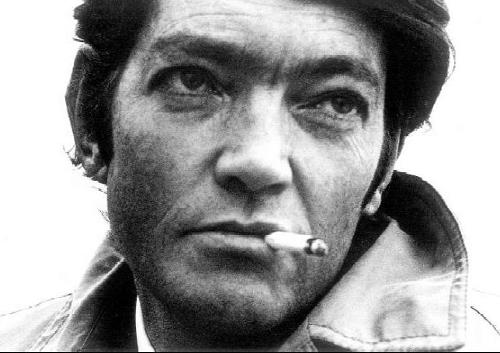

The horror! The horror! Bix is Kurtz! Inarguably, though, Bix is dead. Is that romantic somehow? Just as Bix would likely be unimpressed by the festival that bears his name, so might he have been unimpressed by the idea that his death was anything but “squalid.” That’s Terry Teachout’s word, by the way. I interviewed Teachout earlier this year—on the weekend of Bix’s birthday, it turned out—and he reminded me of a jazz musician’s perspective. “They don’t see themselves as romanticized, self-destructive figures, and Bix Beiderbecke didn’t either,” Teachout said. “He didn’t know what the hell was happening to him, I’m sure. He was a drunk and he was killing himself and he couldn’t help it and he didn’t know why. Sad and pitiful.”

Bix may be “jazz’s Number One Saint” (Benny Green), but is this how you want your kids to behave? Kirk Prebyl doesn’t. He talks to students in Davenport about Bix’s “bad choices,” and the students seem to respond. “I would have followed my dreams (like Bix),” eighth-grader Emily Beard told the Quad-City Times, “but I don’t want to drink.”

Bix, then, is a cautionary tale. He is an excuse for self-help. “Will power alone can’t conquer such tragedies,” the Rev. Richard Wereley, pastor of Davenport’s First Presbyterian Church, explained a year ago during his annual Bix liturgy. “No one understood that better than Beiderbecke. If you’re in the midst of defeat, crippled by personal crisis or abuse or addiction, get help now. Turn to someone who will lift you up.”

Choices, of course, can go either way. “What would music be like if he’d lived to be an old white-haired guy like me?” Prebyl asked.

Where there’s a question, Wikipedia has an answer. In this case, it’s Alternate History Wiki, which posits that Bix sailed through the Great Depression in Benny Goodman’s band, even blowing a masterful, eight-chorus solo on “Sing Sing Sing” at the famous Carnegie Hall concert in January 1938. Then things got really interesting.

In 1943, tired of jazz and the commercial aspects of the music world, Beiderbecke stunned America by announcing his retirement from brass playing and jazz to concentrate on piano and formal music. He moved to New Haven to improve his piano playing and study classical music with Paul Hindemith at Yale, then to California in 1947 to work with Darius Milhaud, then on to Paris for further study. His 7th Symphony, debuted at Carnegie Hall in 1952, was the most acclaimed formal music work by an American performed in that decade. He made only one surprise return to the jazz world, playing on cornet alongside Miles Davis with the Gil Evans Orchestra at the 1959 Newport Jazz Festival, performing music from Bix’s beloved Porgy & Bess. Returning to Paris in 1963, Beiderbecke taught composition, retiring in 1974. He never married.

Certainly not. That would be very un-Bix. He finally died in Paris at the gray old age of 85, one year older than Charlie Parker.***

Would that it were so.

* The occasion for Schjeldahl’s article, by the way, is an exhibit at New York’s Guggenheim called “No Limits, Just Edges: Jackson Pollock Paintings on Paper.” No limits, true, just trees . . . I am reminded that New York was not always so hot for Pollock’s work. How else did his Mural—commissioned for a cocktail party at Peggy Guggenheim’s apartment, it became, according to Leonhard Emmerling, “a turning-point in twentieth-century art”—end up at the University of Iowa?

** Pollock connects to jazz mythically through Bix; he connects directly through Ornette Coleman, who featured “White Light” on one of his album covers.

*** The connections between Bird and Bix are endless (for instance, they both “Live,” apparently), but I like this story, found in Young Chet by William Claxton: “Bird had a rather limited education, but he was extremely bright and quick, and had a way with words. He was very articulate. If he couldn’t find a word to describe something, he would invent one that sounded completely appropriate. So when he coined the term ‘Bixelated,’ it seemed perfectly logical to us. It was during our conversation that I had asked him about Chet Baker. He went on with his answer, “. . . Yeah, that little white cat is kinda Bixelated—you know, a kind of Bix Beiderbecke quality. Reminds me of some of those old Bix records my Mama used to get for me. Like Bix, Chet’s blowing is kinda sweet, gentle, yet direct and honest.’”

[August 3, 2006]