WELL-TOLD LIES

Richard Russo, once a teacher of writing himself, opens his debut collection of short stories, The Whore’s Child, in familiar territory: the classroom. Sister Ursula, who is “nearly as big as a linebacker,” deposits herself in the narrator’s advanced writing workshop, uninvited and unregistered. Despite the professor’s insistence that she write fiction—“In this class we actually prefer a well-told lie,” he tells her—she submits for the class’s consideration several hefty installments of rock-pure memoir.

She patted my hand, as you might the hand of a child. “Never you mind,” she then assured me, adjusting her wimple for the journey home. “My whole life has been a lie.”

“I’m sure you don’t mean that,” I told her.

But of course she did. Sister Ursula is constitutionally incapable of writing what is not true. On the other hand, she is equally incapable of seeing clearly what she writes—and this is what provides Russo’s story, if not the nun’s, the thrum of good fiction.

In a post-modern and un-Russo-like twist, “The Whore’s Child” is both the perfect short story and the blueprint for such a story. As the professor summarizes Sister Ursula’s bitter and lonely take (he provides only her knife-edged first lines, like “It was my hatred that drew me deeper into the Church”), we also hear the class’s response. It is in this unlikely arena, marked by PC angst and academic jargon, that Sister Ursula discovers a secret she has been hiding from herself her entire life.

Sister Ursula, we come to understand, is the ideal practitioner of the “well-told lie.”

Russo’s regular beat, it should be said, is men, not nuns, sons, not sisters. Through five fat, summer-perfect novels, including this year’s Pulitzer Prize–winning Empire Falls, the author has explored, with wonderful humor and pathos, that great American, impotent male. From the down-and-out Sully in Nobody’s Fool to the hapless but good-hearted Miles in Empire Falls, Russo’s protagonists are mere skeletons of the 1950s ideal they were weaned on. Where their fathers lived in an age of straightforward, powerful men, they have reached middle age in a time of ironic self-contempt.

Just ask Hank, who at the beginning of “The Farther You Go” is suffering from a deep, throbbing pain emanating from the center of his being, the result of recent prostate surgery. “There are those who think that a man’s phallus is the center of his being,” he muses, “but I have not been among them until now.” The story that follows lodges Hank square in the eye of his daughter’s domestic squabble. Before it’s over, he’s forced into the uncomfortable position of giving his son-in-law Russell, guilty of domestic abuse and kicked out of the house, a ride to the airport.

Could it be that Hank actually sympathizes with the kid? At least to the extent that he sympathizes with Russell’s total inability to connect with this woman: “That I am a man has somehow escaped her,” mourns Hank, referring to his daughter, “which is why she doesn’t think twice about bending over in front of me in her peasant blouse. And maybe it’s even worse than that. If she has never thought of her father as a man, can she imagine herself as a woman?”

Then there is Martin, poor, pathetic Martin of “Monhegan Light.” On the ferry to an artist’s colony off the coast of Maine, Martin whines about his dead wife’s sister: “Of all the things that Joyce’s sort of woman said about men, Martin disliked the he-just-doesn’t-get-it riff most of all. For one thing it presupposed there was something to get, usually something obvious, something you’d have to be blind not to see.”

It isn’t until Martin discovers a series of nude paintings of his wife, done by her lover, that he finally opens his eyes and gets it.

Russo doesn’t approach his interest in men and their “poor, maligned appendage(s)” with the drum-beating fervor of, say, Robert Bly. Instead, his stories participate in a kind of elegy. The Eisenhower era of liberal-arts educated, war-hewn men in suits is lost, and with it has gone any model for how we men should conduct ourselves.

In “Joy Ride,” a young boy is whisked west by his mother, who is determined to leave her husband and raise some hell. After days of traveling on the interstate, he finds himself on the dance floor, wedged between two men battling over the honor of his mother: a frighteningly obese man who regularly devours record amounts of steak as a promotional trick for a barbecue joint and a rascally come-on artist who doesn’t take no for an answer.

Meanwhile, at home, sits his trickster dad, who at heart seems to have wanted only the best for him and his mom.

Sometimes the characters here are almost too familiar: Hank from “The Farther You Go,” for instance, bears more than a passing resemblance to a stopped-up professor in the novel Straight Man. But Russo spins his tales in prose that is as straightforward as the kind of world his characters long for, full of the crisp and elliptical dialogue he is rightly famous for.

Six years ago, the philosopher-writer William H. Gass issued a diatribe declaring that “the Pulitzer Prize in fiction takes dead aim at mediocrity and almost never misses; the prize is simply not given to work of the first rank, rarely even to the second.” It’s worth wondering whether Empire Falls was truly the finest American novel of the last year. Still, Russo’s easy-going, accessible literary style, imbued as it is with so much humor, is often mistaken as lightweight.

The Whore’s Child suggests, once again, that such critiques are little better than well-told lies.

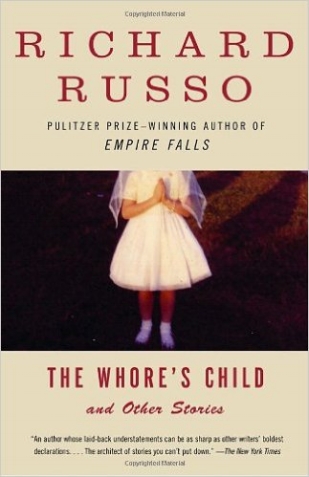

The Whore’s Child by Richard Russo (Knopf, 240 pages)

Concord (NH) Monitor, July 2002