ROMANCE AND SUICIDE BOMBS

The heart of Israeli artist Rutu Modan’s new graphic novel Exit Wounds can be found in the wreckage of suicide bombs, but it equally can be found in the wreckage of love gone bad. “I remember when I was in my twenties, I once dated a guy who never called me back,” the author recalled in an interview with Maisonneuve Magazine. “After a few days, I decided that he was probably dead. I couldn’t understand why he hadn’t called me.”

Drama, even trauma, is preferable to a missed phone call apparently.

Now meet Numi, a young Israeli soldier who is convinced that an unidentified, unclaimed, unrecognizable body left over from a suicide bombing in nearby Hadera is her lover Gabriel. She is so convinced, in fact, that she tracks down the man’s estranged son, Koby, so that together they might find the truth. Koby, as one might imagine, is skeptical. He has never heard of Numi. And a day without a phone call from Gabriel is a day he seems to prize.

“Is there some reason you think it’s him?” Koby wants to know, as he slouches on a park bench, angrily flicking ash from a cigarette.

“Look, it’s kind of difficult to explain.”

“Why don’t you try.”

Numi does try, but it’s a long story and one that remains obscure even by novel’s end. Luckily, the details aren’t important; neither, ultimately, is whether Gabriel is alive, dead, or trapped somewhere inside his preternaturally filthy apartment. Instead, Exit Wounds is about all of the things you expect it’s going to be about: the dysfunctions of family, the dysfunctions of people blowing themselves up at train stations. Modan doesn’t seem to have anything new to say about this, yet the fledgling romance she delivers between Koby and Numi is so fraught, so furtive, so utterly convincing, that it redeems the entire book.

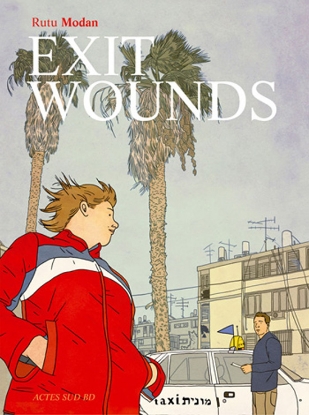

Credit in part Modan’s deft artwork. She draws a Numi who is tall, hefty, and androgynous, hiding her body in baggy jeans and an overcoat. Koby, meanwhile, maintains a posture of indignant pain, hunched over, a never-ending cigarette dangling defensively from his mouth. Modan’s characters feel three-dimensional this way, without too much belaboring exposition. When Koby first meets Numi, physical attraction is hardly even a consideration—he might find it repugnant even, as he does so much else—yet it can’t go unnoticed when, on a trip to interview a witness to the bombing, Numi wears a skirt and blouse for the first time.

Their conversation in the car rehearses many of Koby’s own grievances and insecurities, which become less and less sympathetic by the page. Age differences are a problem for him (especially when imagining his own father with Numi), but so is money (Numi has too much, it seems), so is a soccer jersey he got for his eleventh birthday (it was the wrong team). One is tempted even to root against Koby. If the absent Gabriel seems neglectful and cold, Koby comes across as petulant and childish. Get over it, someone needs to tell him. It’s just a jersey. And your dad might be dead!

But death is something no one wants to talk about. How ironic that after two deadly bombings, the streets of Tel Aviv, bathed in Modan’s lush watercolors, should look as tranquil as they do on the first page. Koby, a cabby, is actually yawning. Later, a clerk at the morgue smiles routinely as she clarifies which bombing Koby and Numi have inquired about. Another bombing witness sells flowers as he talks about the event. “It’s a miracle I’m still alive,” he declares, a big smile on his face, too. His obliviousness is calculated, however.

“This happens in Israel,” Modan said in her interview. “People close themselves off from [death and politics] in order to cope … People just stop thinking about it, but as much as you try to ignore it, it increasingly becomes a part of your private life.”

Would that Koby and Numi were closed off only to death and politics. But their search, their stuttering romance, their uncertain future all suggest a willingness to at least try to open up. That this requires, in its own way, a repudiation of Gabriel, the very one for whom they spend the book searching, is Exit Wound’s final and most satisfying irony.

Exit Wounds by Rutu Modan (Drawn & Quarterly 160 pages)

Colorado Review, 2007