ODD, EXHAUSTING, AND BEAUTIFUL

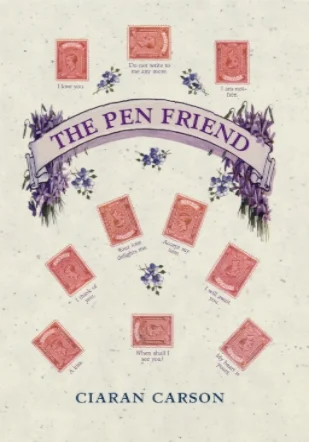

It depends on what you’re looking for in a literary companion. Gabriel Conway, the protagonist of Ciaran Carson’s slim but dense new novel The Pen Friend, is a little fussy. He’s obsessed with fountain pens and coincidences, Andy Warhol and iconography, the mystical associations of Esperanto. He knows a lot about birds. And as the book opens, he has just received a postcard from a former lover. “It’s been a long time,” she writes in the first of thirteen short, often cryptic messages that she mails to Gabriel over the course of several months. Or at least he assumes they’re from her. She never signs her name or includes a return address, but in the first of his rambling epistolary replies Gabriel notes “that we read handwriting as we do faces, and yours—your handwriting, I mean—had changed little, even though it was over twenty years since we had last met, and parted. Not that I believed it was yours at first; for if seeing is believing, sometimes we look and do not see; and sometimes we only see what we want to see, or what we want to believe.”

From there he riffs on the ways in which we are contained in our handwriting so that even when we try to disguise it, “some ineradicable loop or slant, an identifiable arpeggio, betrays us.” This experience—of something hidden and then revealed—is like running into someone you haven’t seen in years, Gabriel argues, someone whose name you’ve forgotten but who you insist hasn’t changed a bit. And then you finally manage to remember the name—of course!—and “now the evidence is unmistakeable, and we read the face like invisible writing that blooms to the surface when exposed to heat.” All of which is to say that his still-unnamed lover’s handwriting reveals her character much the way her name will, assuming, that is, it ever blooms to the surface. “I knew its physiognomy,” Gabriel writes. “As you would have anticipated. The words are written in fountain pen, and in blue ink, the colour of eternity.”

Oh brother. Don’t get Gabriel started on fountain pens: “You knew I would remember that a fountain pen first brought us together, all those years ago.”

As I said, it depends on what you’re looking for in a literary companion. Gabriel is no man of action; in fact, he does nothing in The Pen Friend except write, and one can imagine a stack of books piled high on his table—something on the Dutch masters, an etymological dictionary, a turgid history of pens—available for consultation and, when necessary, quotation. Toward the end of the novel he recalls a time he almost takes action, an incident upon which everything depends, actually, but that’s about it. He’s not particularly ironic, except in a deeply literary way. Nor is he a job lot of predictable neuroses. Rather, Gabriel is a collector (of pens, of words, of stories, of languages). And although he works at an art museum, he, like Carson, is at heart a poet. Blooms to the surface is just gorgeous and representative of the sort of imagery that reveals itself to the patient reader on almost every page.

The outline of a thriller-like plot, meanwhile, shimmers just below the surface. Gabriel’s lover seems to have been involved in a British spy ring called MO2, and there’s something decidedly creepy about the way her postmarks home in on his native Belfast, Northern Ireland, as if she were stalking him. As if he were prey. Was their romance ever real or was it just a bit of mission creep? Sometimes we only see what we want to see. For much of the novel, though, the plot disappears behind a tangled thicket of Gabriel’s thoughts, which are busy blazing connections between, for instance, Billie Holiday, née Eleanora Fagan, who is said to have taken her name from the actress Billie Dove; suicide, as too often provoked by “Gloomy Sunday,” sung by Billie Holiday; the Dutch company Unilever, which manufactures Dove deodorant; and “the intertwining doves of the L’Air du Temps bottle that sits on your dressing table”—a perfume manufactured by Nina Ricci in 1948, the year of Gabriel’s birth and of Carson’s, the year of Nina’s parents’ wedding (the lover’s name is Nina, finally, except that it isn’t; her father is Dutch, her mother committed suicide); and of the design of the fountain pen with which Gabriel is writing at the moment—“which is possibly neither here nor there,” he concludes, “though it could be argued that any one thing in the universe implies the existence of every other thing.”

The Pen Friend is odd, exhausting, and beautiful, and it has arrived in the United States, perhaps unsurprisingly, with a thud of silence. Although brilliant and criminally underappreciated, Ciaran Carson suffers from a) being primarily a poet; b) being a foreign poet at that; and c) writing prose that, while not poetry, is odd and exhausting. For the last twenty-five years he has written over and over again of his native Belfast, of his Catholic upbringing, and even of the Troubles, but without engaging in the sort of tropes that are most familiar and most tempting to Irish Americans. It is true that a stray bullet once almost killed Carson, but you won’t find that story in his books; instead, you’ll encounter his obsession with the arbitrary, and how we might carve bits of meaning from it. It is true that British soldiers repeatedly have thrown Carson against walls and demanded to know what he is called and where he is from, but you won’t find that in his books, either; instead, you’ll encounter, time and again, his fascination with names and his anxiety about place. By his own admission, Carson isn’t even writing to be read. An interviewer recently asked him if he thinks much about “entertaining” his audience. “No,” he replied. “If there is an audience it’s my wife. It’s enough for me.”

And yet the more you read Carson, the more you find yourself slipping comfortably into this strange universe of his, a place where Billie Holiday connects to Dove deodorant and where any one chapter of The Pen Friend implies the existence of everything else that Carson’s written. In fact, the more famous iteration of this idea of all-connectedness can be found on page twelve of Carson’s previous novel, Shamrock Tea, in which another Carson-esque narrator, this one actually called Carson, muses on the philosophy of Sherlock Holmes: “To a great mind, says Holmes in A Study in Scarlet, nothing is little; and from a drop of water, he maintained, a logician could infer the possibility of an Atlantic or a Niagara, without having seen or heard of one or the other; for all life is a great chain, the nature of which is known when we are shown a single link of it.”

This is a classic instance of a novel instructing you in how to read it, for Shamrock Tea—the same as The Pen Friend—constructs just such a chain, with Carson using colors instead of drops of water or fountain pens to reveal a universe populated by Christian saints and Roman gods, by his uncle Celestine and his cousin Berenice, by unicorns and bees; Napoleon, Augustine and Oscar Wilde; by Holmes and his creator, Arthur Conan Doyle; by the fifteenth-century Dutch painter Jan van Eyck and the twentieth-century philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein; by the neighbors in the narrator’s fractious home of Belfast and the thousands of insane inhabitants of the Belgian town of Gheel. It’s amazing, frankly, to watch Carson assemble 101 two-and-a-half-page chapters, each with a mind of its own, into a sensible, let alone a mischievous and often funny, narrative. He’s a magician, and indeed the titular tea is a trippy potion that allows Carson and his cousin to actually step into van Eyck’s famous Arnolfini Portrait; it also provides some hope, however drug-induced, of binding together the warring factions of Belfast.

In his masterful Austerlitz, W. G. Sebald wrote of how night creatures, such as possums and raccoons, possess “strikingly large eyes, and the fixed inquiring gaze found in certain painters and philosophers who seek to penetrate the darkness which surrounds us purely by means of looking and thinking.” The insight is hardly new: that in the dark our eyes grow larger, struggling to make connections between unseen objects; that in this struggle to see and understand, we create from our imaginations a whole new world. It also happens to serve as a perfect summary of Carson’s work. Sometimes we look and do not see. Sometimes we see what we want to believe. In Shamrock Tea Carson makes the point using a honeybee: “The seething comb of black and amber bodies seemed without purpose, but he knew that this was far from the case: by dancing, by touch, by scent, by the vibrations of their wings, bees communicated a map of the immediate nectar-bearing countryside.” And they do all this, Carson explains, with eyes that operate on “a high flicker-fusion frequency.” In other words, their vision consists of “isolated frames connected by darkness.” It’s up to the bee, then, to connect the dots.

Carson’s artistic vision is both poignant and challenging, but it’s also frustrating. What connects the dots—in The Pen Friend and in Shamrock Tea—can sometimes seem arbitrary, shallow, even paranoid. Carson acknowledges the problem in “The Queen’s Gambit” from Belfast Confetti. Complaining of Troubles-era pundits who reflexively reach for pre-determined narratives of oppression, he observes the large number

Of Nines and Sixes: 1916, 1690, The Nine

Hundred Years’ War whatever

Or maybe we can go back to the Year Dot,

the nebulous expanding brainwave

Of the Big Bang, releasing us and It and

everything into oblivion ...

The next line of Carson’s poem contains the words, in italics, “It’s so hard to remember, and so easy to forget,” words from an old Billie Holiday song that also show up, in various forms, in The Pen Friend. Perhaps the Year Dot represents that moment when we all forget—but forget what? What is the truth that Catholics miss when they trace their grievance back to the Famine or to Cromwell? Or, put another way, when Protestants light bonfires on the anniversary of the Boyne, are their nines and sixes any less valid, any less paranoid, than when Carson finds meaning in the coincidence of recurring doves?

Just as the best literature tells us how to read it, so it tells us how to argue with it; it contains the germs of its own criticism. When reading Carson’s prose it’s easy to become impatient with the game of coincidences and connections. Gabriel receives a postcard inscribed with the words “It’s easy to remember”; on the reverse is pictured the Japanese hanging-scroll painting Two Dutchmen and Two Courtesans. This helps him remember his and Nina’s first date (Dutch treat), a reverie that leads him to muse on her Dutch last name (once Bouwer, since changed to Bowyer), and her father Arie Bouwer, who served in the Dutch resistance during the Second World War and whose nom de guerre was Harry, a kind of hiding-in-plain-sight that provokes mention of Poe’s “The Purloined Letter.” Turns out Gabriel’s Merlin fountain pen is Dutch-made and colored like the plumage of the bird for which it was named, and oh, did you know that pen derives from the Latin penna for feather or quill? No wonder so many pens take the names of birds, just as Rolls Royce, during World War II, built engines for De Havilland Mosquito aircrafts and called them Merlin. And it was those Merlin-powered Mosquitoes that made forays over Europe, including a bombing run, ordered by a “Harry,” on the Dutch agency that filed identification cards.

Carson quotes Edvard Munch: “We see with different eyes at different times. We see one thing in the morning, and another in the evening, and the way one views things depends on the mood we’re in.” Listening to music is much the same, as Carson, a traditional flute player, argues in Last Night’s Fun, his typically eccentric celebration of Irish music: “In any session of music, no one will hear the same thing: it will depend on context, on placement, on experience—whether or not you’ve heard the tune before, whether or not the person next to you knows the tune that you might only half-know.” Meanwhile, Gabriel (the pen-collector) frequents an antique shop whose proprietor invents stories to explain the artifacts he sells, stories that change as the situations of objects shift. A watch and a pistol might combine for a breathless tale until the watch sells and a new backstory evolves. After all, “things in real life change all the time, even when they stay the same. Depends on the way you look at them.” And it’s from this antique dealer that Gabriel purchases L’Air du Temps, by Nina Ricci, the namesake of Nina, whose actual name is Miranda but whom Gabriel for a while thought was Iris.

Oh brother. Don’t get Gabriel started on Iris. The Greek god of rainbows. The iridescent plumage of a bird. The flower that in Ancient Egypt symbolized eloquence. The iridium tip of fountain-pen nibs.

I suspect that readers either love this sort of thing or, more likely, find it wildly beside the point. After all, for a novel to be satisfying, shouldn’t it deliver character and plot, not erudition? So who is Gabriel? And who is this woman he once loved, good old What’s Her Name? At times she doesn’t feel real; she feels magical, caught between worlds. In the introduction to his translation of the ancient Irish epic The Táin, Carson notes that much of the story’s action occurs at fords: “In Irish mythology, streams and rivers are liminal zones between this world and the Otherworld ... a metaphysical space, a portal and a barrier, a place of challenge.” The Belfast of Carson’s youth was such a place, partitioned as it was between Catholics and Protestants, and knowing this helps to explain Carson’s recurring interest in surveillance, ambiguous identities, borderlands, and crossings. In “Belfast Confetti,” the writer complains of the familiar “labyrinth” of dead-end streets—“Balaklava, Raglan, Inkerman, Odessa”—from which he can’t escape and where “every move is punctuated.” “What is / My name?” he wonders. “Where am I coming from? Where am I going? A fusillade of question marks.”

These persistent questions, even confusions, of identity, while they may not satisfy all readers of The Pen Friend, are indeed the point. And they are intimately tied not just to geography and religious identity but to language itself. Like Gabriel’s, Carson’s father was a native English speaker who taught himself and Carson’s mother Irish, and then raised Carson and his siblings as native speakers. Carson learned English as a foreign language, but now, as he has repeatedly observed, it’s his Irish that feels foreign. Perhaps that’s why he has written so compellingly—as in his forewords to The Inferno of Dante Alighieri and The Midnight Court—on the subject of translation and, in particular, the translator’s imperative to patrol the border between languages. Carson’s rendition of Dante’s trip to hell sheds the terza rima and the Italian, but it is not, nor should it be, fully English lest it shed Dante as well.

Writes the Irish poet Eavan Boland:

a new language

is a kind of scar

and heals after a while

into a passable imitation

of what went before.

She is referencing not the act of translation but the unprecedented (and remarkably speedy) process by which Ireland in the nineteenth century shed its native language for that of its colonial masters. The violence implicit in her image suggests a cultural rupture that’s everywhere in Carson’s writing, just as it was everywhere in Carson’s youth. In Belfast, Irish marks you with the tri-colored tongue, its vowel-ish, guttural sounds revealing identity like the invisible writing blooming to the surface. Of course, it was an identity that could get you killed, and Carson père, who so actively embraced Irish, also spoke Esperanto, an invented language designed to overcome such Troubles. And yet the younger Carson never cottoned to it. He seems to relish the in-between spaces. With a name half-Catholic, half-Protestant, he is content to hang out at the ford, to wade in the ambiguities, the almost possible.

In the end, The Pen Friend is surprisingly effective as a novel. When a bomb goes off in a café, it showers the narrative with a kind of Belfast confetti, shrapnel-sharp questions that lend the story of Gabriel and Nina a new urgency. Still, to call The Pen Friend a novel perhaps misses the point. Carson is less interested in the trappings of character and plot than he is in the strange, often magical connections of language. They allow him to piece his Belfast back together, bit by bit, into something new.

Just don’t get him started on pens.

The Pen Friend by Ciaran Carson (Blackstaff Press, 256 pages)

VQR, 2010