Jefferson's Shadow

Brendan Wolfe

i.

John Stewart Bryan (Courtesy of the Richmond Times-Dispatch)

In the spring of 1921 the University of Virginia hosted a celebration of its first hundred years. The event had been delayed two years because of the Great War, so when Rector John Stewart Bryan rose to speak on the steps of the Rotunda it was with the awful costs of that victory in mind. He was there to unveil a plaque in honor of students and alumni who had been killed, men like the football great Buck Mayer and the charismatic king of the Hot Feet, James Rogers McConnell, for whom the Aviator statue had already been dedicated.

He began his address by noting the names of the university's 550 Confederate dead, "those who marched forth under the flag of Virginia and died in the defense of their homes," and asking that his audience treat "their fourscore younger brothers" with the same respect.

"The sad sagacity of age has taught us that nothing built with hands can 'hold out against the wreckful siege of battering days,'" Rector Bryan said, quoting Shakespeare, "and yet we place this tablet on the walls of this century-old Rotunda in response to a wish that lies deep in the heart of humanity. That desire to enshrine beloved memory beyond the changes and chances of time is one that has come to all men everywhere. Every heart has its inner shrine."

Bryan was the publisher of the Richmond News Leader, one of the premier newspapers in Virginia, and his editor was Douglas Southall Freeman, who would later write a seven-volume biography of George Washington and, in 1935, win the Pulitzer Prize for his four-volume biography of Robert E. Lee. The patriotism these men felt toward the United States, the Confederacy, and, in Bryan's case, the University of Virginia, was pure, uncomplicated (at least to them), and supremely confident.

Members of the Class of 1861 on Grounds for the centennial in 1921 (Courtesy of University of Virginia Special Collections)

After praising Virginians' "aptitude for command and their instinct for war," and after summoning for his audience memories of Valley Forge, Chapultepec, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg, Bryan hailed the university as essential to this tradition. Its students "had eaten the bread of Virginia in which lived[,] transubstantiated[,] the soul and body of the whole nation."

Bryan mentioned Thomas Jefferson only in passing, but the University of Virginia's founder was at the center of the four-day centennial event. Three thousand alumni, the state's governor, nineteen delegates from ten foreign countries, and more than a hundred representatives of colleges and universities from around the world all found occasion to ponder and praise Jefferson who, as an intellectual, represented the other side of Bryan's vision of Virginia. The university "was founded by a lover of human freedom whose political philosophy was based upon absolute faith in the ultimate wisdom and integrity of trained men," Edwin Anderson Alderman, the school's first president, told the assembled delegates, as reported by the Daily Progress newspaper. "Guided by sincere scholars," surrounded by "opulent beauty" and "fair landscapes," it has spent the last century in "fruitful pursuit of justice in society and truth in science."

In association with the centennial, the university also commissioned an exhaustive, five-volume history of itself, published in New York by Macmillan and subtitled The Lengthened Shadow of One Man. Its author, the historian Philip Alexander Bruce, pays tribute to Jefferson throughout, imagining the old man watching the construction through a window in the Rotunda and then presiding over this great new institution, even in death, as a kind of shadow. On the final pages of volume 5, Bruce assures his readers that the school "has never swerved in loyalty" to Jefferson and his teachings, and promises that it currently "upholds,—and we believe will continue to uphold,—the general principles of our race."

"During the last one hundred years," Bruce concludes, "the majestic shade of that founder has seemed to brood above his beautiful academic village." He's there "to warn, to guide, and to inspire," a monument to "the exquisite refinement of his taste" and "the absolute correctness of his foresight."

ii.

Now fast-forward a hundred years, almost. And somehow I am playing the unofficial and informal role of bicentennial historian, having authored Mr. Jefferson's Telescope: A History of the University of Virginia in 100 Objects and helped to curate a major new exhibit based on the book at the University of Virginia Library. A reporter has called and wants to know my thoughts on where UVA stands today.

In late September 2017 ...

A couple months after the Ku Klux Klan marched in defense of a Stonewall Jackson statue that was dedicated in Charlottesville the same year as the centennial ...

A few weeks after neo-Nazis night-marched on the Lawn, tiki torches ablaze, and, the next day, murdered a young woman and injured dozens more near the Downtown Mall ...

And not long after protesting students threw a black shroud over a statue of Thomas Jefferson himself on the north side of the Rotunda. In a statement circulated the next morning, the university's president accused them of "desecrating ground that many of us consider sacred."

What do I think? Oh, man.

iii.

"Every heart has its inner shrine."

iv.

From the Raleigh (North Carolina) Minerva, October 31, 1817, page 4 (Courtesy of Newspapers.com)

The University of Virginia's bicentennial officially begins on October 6, 2017, the two hundredth anniversary of when Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe gathered to dedicate the cornerstone of what would become Pavilion VII. The school, then called Central College, was chartered as the state university a little more than a year later.

About halfway through volume 1, Philip Alexander Bruce describes the morning of October 6, 1817, as "at first fair, but the clouds later on began to gather;—happily, however, only to disperse and leave the weather clear again." He notes, curiously, that the county and superior courts were in session and when the judges "were informed of the impending event," they, and all those scheduled to appear before them, quickly "repaired to the scene." Had they not known ahead of time that two former presidents and the incumbent were to be in town? Whatever the case, Bruce tells us that "the doors of all the stores were locked, private houses shut up, and the entire population of the little town darkened the road to the College."

There they witnessed a ceremony with full Masonic rites, led by Lodges 60 and 90 of the Society of Freemasons. "President Monroe applied the square and plumb," Bruce writes, "the chaplain asked a blessing on the stone, the crowd huzzaed, and the band played 'Hail Columbia.'"

Edmund Bacon (Courtesy of the University of Virginia Special Collections)

Edmund Bacon was there. The overseer of Jefferson's slaves at Monticello, he recalled that after President Monroe laid the cornerstone and pronounced it square, he and a few others made short remarks. As for "Mr. Jefferson—poor old man!—I can see his white head just as he stood there and looked on."

It's odd how passive and almost marginal Jefferson is in the scene. This college, soon to be a university, was one of his life projects. Back in 1786, he had written to his mentor George Wythe from Paris about the importance of public education. "No other sure foundation can be devised for the preservation of freedom, and happiness," he declared. "If any body thinks that kings, nobles, or priests are good conservators of the public happiness, send them here."

Jefferson understood which way the wind blew; an angry mob stormed the Bastille just three years later. He also had his blind spots. Slaves, after all, built the university. That's at least in part why his overseer was on the scene: to supervise the ten enslaved men who had been clearing the several hundred acres of what until recently had been President Monroe's cornfield. The next day the college's board of visitors instructed the proctor "to hire laborers for leveling the grounds and performing necessary services for the works or other purposes." Many, if not most, of those laborers were enslaved, and over the next nine years they finished clearing the land; hauled, cut, and nailed timber; molded and fired bricks, such as the one used for the cornerstone; transported quarried stone; and participated in nearly all other activities related to the building of the university.

Sally Cottrell Cole, an enslaved woman who labored at the University of Virginia (Courtesy of University of Virginia Special Collections)

In November 1818, an enslaved man called Carpenter Sam began tinwork at the site and eventually contributed to the construction of two pavilions and three hotels. In May 1820, an enslaved man named Elijah began hauling quarried stone, and in February of the following year the slave William Green was hired to perform blacksmithing duties. Slaves manufactured between 800,000 and 900,000 bricks to be used in the construction of the Rotunda, a domed building that was the focal point of the Academical Village and would serve as the university's library.

When the university opened for classes in 1825, enslaved African Americans (and a few who were free) cooked and served food, washed and mended clothes, started fires and cleaned shoes, swept the floors, made beds, and carried away ashes; they painted and whitewashed, fetched ice and wood, and ran general errands. They exhumed bodies for dissection—usually African American bodies—and, perhaps most famously, rang the bell that kept time on Grounds.

Enslaved African Americans, in other words, did the work of this foundation for the preservation of freedom. Bruce mentions their labor in volume 2 but worries it was "slipshod" and "lazy," and he blames slaves for spreading disease. They were not mentioned once at the centennial or in Virginius Dabney's 642-page Mr. Jefferson's University: A History, which was published in 1981.

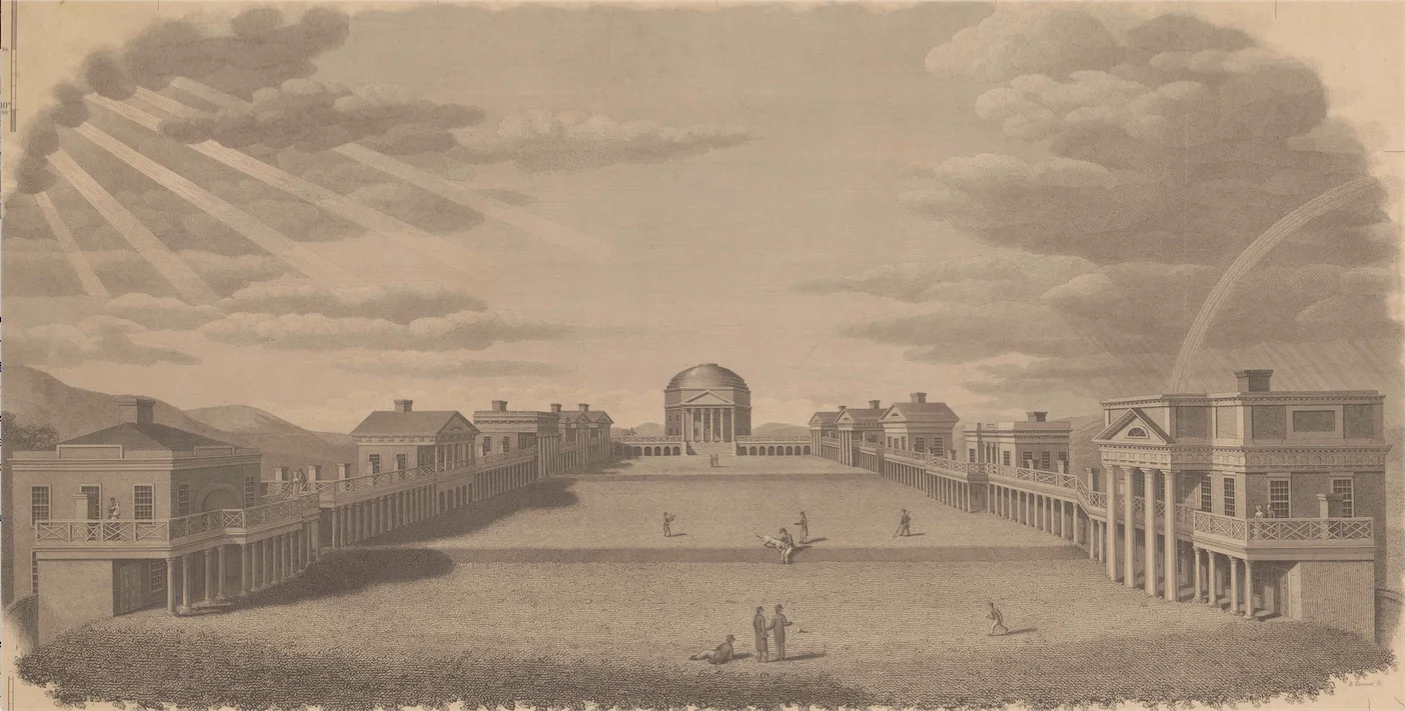

The Rotunda and Lawn at the University of Virginia, 1827, by the engraver B. Tanner (Courtesy of University of Virginia Special Collections)

v.

They were there, though. Somewhere beneath all the sunshine and rainbows ...

But only if you look closely ...

vi.

"Every heart has its inner shrine."

vii.

I'm silent for a moment as the reporter waits patiently on the other end of the line. What do I think about where UVA stands today? I bring the conversation back to history again, to something I noticed while working on my book. Jefferson founded the University of Virginia as a bulwark of freedom; about that there is little doubt. But other principles implicitly served as institutional cornerstones, too. They were there at the beginning and are still there, no matter how profoundly the university changes. "They're baked in the cake," I say.

Take, for example, the story of Caroline Preston Davis. In 1892, she petitioned the university for admission, forcing the board of visitors to consider the possibility of accepting women as students. Colleges and universities in the United States had been admitting women since Oberlin College opened in 1837—founded by abolitionists, Oberlin also accepted African Americans—so that by the 1890s, about two-thirds of American universities were coeducational. Nothing in the act that had chartered the University of Virginia in 1819 limits enrollment to men, but Thomas Jefferson was known to have been skeptical of educating women.

Martha Jefferson Randolph (Courtesy of University of Virginia Special Collections)

To be fair, his daughter Martha Jefferson Randolph had been one of the best educated women of her day. In a 1783 letter, Jefferson had sketched out for his then-eleven-year-old a rigorous, seven-day-a-week schedule that consisted of music, dance, drawing, letter-writing, French, and English literature, all of which was intended, he wrote, to "render you more worthy of my love."

And to win a husband.

Only in the instance that said spouse turned out to be a "blockhead"—the chances of which Jefferson calculated at precisely fourteen to one—should her education be applied to what the Virginia gentry considered to be the male sphere of activity. This included running a plantation and engaging in commercial activity.

Why else might a woman need, say, mathematics, which Martha had studied in Paris?

As it happens, math is the subject Caroline Preston Davis wished to pursue. The historical record says little of Davis, who in 1892 was about twenty-seven years old, but she had a distinguished pedigree. Her grandfather, John A. G. Davis, was a professor of law at the University of Virginia and the husband of one of Jefferson's grandnieces. In November 1840, Davis was shot dead by a student outside his home, Pavilion X, but he left behind four sons, all of whom attended the university. Among these were Caroline Davis's father, the Reverend Richard Terrell Davis, known during the Civil War as the "Fighting Parson," and John Staige Davis, a beautifully coiffed professor of anatomy. (Another relative of hers: the historian Virginius Dabney, whose great-great grandfather was the murdered professor.)

Perhaps feeling pressured by these connections, the board of visitors discussed the matter on June 27, 1892, and decided to accommodate Davis's request. While it would be "impracticable and inexpedient" to get into the business of educating "young ladies," the board declared that it would be "practicable and expedient" to bend the rules where (white) women of "good character" were concerned. As long as they showed "adequate preparation" and paid the same fees as other students receiving actual diplomas and attending lectures, such women would be allowed to study privately with a professor and, upon passing his examination, receive "a certificate in appropriate form, of that fact, to be conferred by the Faculty."

One of the hundred objects in my book is Caroline Preston Davis's certificate. Dated June 14, 1893, it's not a diploma, as you can see. The word "GRADUATE" has been crossed out and the university seal removed.

(Courtesy of University of Virginia Special Collections)

viii.

Just a year later, at its June 11, 1894, meeting, the board of visitors abruptly changed its mind. While claiming to be "in full sympathy with the movement" to educate women, the university lacked the "proper facilities" for such a venture. Besides, the board argued, "coeducation therein was never contemplated by the founder of the institution." So why start now?

Forthwith women would no longer be admitted to the University of Virginia as students and any provisions for such were hereby rescinded.

Philip Alexander Bruce (Courtesy of the Virginia Historical Society)

In his fourth volume, Philip Alexander Bruce suggests that the faculty's debate of the issue was wide-ranging. Women, as tax-paying citizens, claimed the right to be educated at Virginia's state university. "Negroes also were tax-payers," Bruce writes, summarizing the professors' response; "and yet their exclusion was never a subject of dispute." And while it might satisfy certain claims of equality if women were to be admitted, their educations would be as useless as Martha Jefferson's, only serving to distract them from their proper duties in the home.

Also catching the eyes of faculty members was a fresh bit of scientific scholarship. Bruce fully quotes the faculty report on this point: "According to medical authority, the strain on young women in severe competitive work (in the higher schools of learning) does often physically unsex them, and they afterwards fail in the demands of motherhood."

He somberly concludes that while this was bad enough, it also raised concerns of "race preservation."

I've always been struck by the fact that Bruce finds no need to explain what he means by this. His audience understood perfectly well: Only white women were being considered for higher education, and if white women were to be "physically unsexed" by the experience, then they would have fewer children than their black counterparts. This might eventually result in a majority African American population or even the disappearance altogether of the white population.

Apprehensions such as these were hardly new to Virginia. They were the subject of speeches before the General Assembly in the aftermath of Nat Turner's revolt in 1831 and continue to preoccupy the neo-Nazis who marched this past August on the Lawn.

ix.

"... desecrating ground that many of us consider sacred."

x.

"That's what I mean by they're baked in the cake," I say to the reporter. "These principles—besides the idea that public education was crucial for the 'preservation of freedom'—they date back to the founding of the university. I kept encountering three of them as I worked on the book, three of them in particular, and they're all there in the story of Caroline Preston Davis. One, the exclusion of women. That's pretty obvious. Two, elitism."

"How does elitism figure into it?"

"Well, from the beginning the University of Virginia was a training ground for gentlemen, for the leaders of men but also the owners of men. Even for that half a minute when the board allowed the admission of women, it was only women of 'good character,' a euphemism for women of a certain social rank—who could pay the fees, who came 'prepared.' The university was not then, and never has been, for just anybody. And the third thing, of course, was white supremacy. It shows up everywhere. In the building of the school, sure, but even after the abolition of slavery, it crops up in an otherwise completely unrelated discussion about the admission of women."

"It's baked into the cake."

"Exactly."

xi.

Colgate W. Darden (Courtesy of the Library of Virginia)

Colgate W. Darden was perhaps the first University of Virginia president to imagine a student body that extended beyond the top tier of elite white men. After serving in Congress and as governor, he came to Charlottesville in 1947 with the idea of democratizing Grounds. "During the next twelve years he rejuvenated the university," writes the historian Ronald L. Heinemann. "Attempting to make it a more democratic institution—over the objections of many students, some of whom burned a cross on his lawn—he encouraged the enrollment of public school students, diminished the role of fraternities, and constructed a student activities building. When a faculty member accused him of trying to make the university 'a catch-all for everybody who wants to go to college in the state,' Darden replied, 'That's what it's supposed to be.'"

And yet that's not at all what it was supposed to be. Not in Jefferson's time. Not in the years leading up to Darden's tenure.

To see how the anxiety that stemmed from Darden's policies played out, and how it mixed with other historical concerns, look at four consecutive editions of the Cavalier Daily, UVA's student newspaper, from the spring of 1954.

FRIDAY, MAY 14, 1954

Just before the annual Easters party weekend, the Cavalier Daily published a satirical story, the very premise of which was that the University of Virginia is something different from a typical state university. At the story's root was a fear of certain kinds of change.

TUESDAY, MAY 18, 1954

After an off day on Monday, the next issue of the paper seemed to confirm these fears when it announced the U.S. Supreme Court's decision, in Brown v. Board of Education, that the separate-but-equal segregation of public schools is unconstitutional. In an editorial, Frank M. Slayton writes, without irony: "To many people, this decision is contrary to a way of life, and violates the way in which they have thought since 1619. Because the Supreme Court has said 'Thou Shalt Not,' it does not follow that the people of the South will adopt a new set of mores as easily as a man changes his coat."

WEDNESDAY, MAY 19, 1954

The next day, another urgent issue occupied the mind of Editor Slayton, although it's difficult to understand, from reading the paper only, what exactly was going on. Titled "Unwarranted Political Pressure," his editorial mentions "the dismissal of eleven students from the University" but does not explain the circumstances. Instead, Slayton worries that some of the punishments meted out by Darden may have been light due to the status of those involved.

One has to consult other sources to find out that in April an all-night party on the East Lawn, attended by eleven male students, one recent male graduate, and a nineteen-year-old woman, resulted in what appeared to have been a gang rape. After being contacted by the woman's parents, President Darden reported that "the girl had come home that day in a dazed condition, apparently beaten and brutalized, covered with bruises." The words "rape" and "assault" were never used by Darden or the board of visitors to describe the incident. The Cavalier Daily never mentions the victim at all. The historian Virginius Dabney refers only to the "sex" scandal, always with the scare quotes.

Both the woman and at least some of the men accused of attacking her hailed from prominent and powerful families, and when an investigation resulted in expulsions and suspensions—civil authorities were never involved—the all-male student body, minus Frank Slayton, erupted in protest.

THURSDAY, MAY 20, 1954

Almost as a gesture of reassurance, the Cavalier Daily on this day reprinted an essay by an instructor in the history department paying homage to the university's hallowed founder. In a section called "Shadow of One Man," the writer notes that "Charlottesville has changed much since 1826 when Mr. Jefferson finally left it. But it has changed as he would have wished. Thomas Jefferson was a modern man. 'The earth belongs to the living,' he once declared, and his life was devoted to the betterment of the living—for his own time and for the generations which would follow."

xii.

On the one hand, the university's second century has been marked by fierce challenges to Jefferson's vision, racial and otherwise, and to the "absolute correctness of his foresight": the admission of the first African American student in 1950, the acceptance of women on equal terms as men in 1970, and a more generous definition of what it means to be worthy of an education at UVA.

On the other hand, until recently the university community has mostly held on tight to the iconic Mr. Jefferson. "Every heart has its inner shrine"—home to its truest sympathies, a place that will be defended at all costs.

While I was working on my book, I asked a historian associated with the university to read the manuscript and alert me to any factual errors. He printed out several pages of notes and across a large wooden conference table we discussed them one by one. In several places he objected to my treatment of race. Slavery, he told me disapprovingly, has become "fashionable" among historians, and too many people are too often "whiny" about what they consider to be negative aspects of the university's history.

His greatest concern, however, was mention of the alleged gang rape from 1954. "It was not rape," he said to me, leaning in, his voice lowered. "The girl had a problem. She was somebody who had made the rounds up and down the East Coast, going to all the schools. And in addition to liking to have sex with everyone, she liked to be slapped around. So the complaint to Mr. Darden was essentially that she came back from that weekend in Charlottesville more beat up than she had been at Yale the weekend before."

I left the meeting shaking. The alleged rape eventually was excised from the book, but for different reasons.

xiii.

"I get it," the reporter says, "but I'm still not sure where that leaves UVA today. The bicentennial is in a few days, so what does your book have to say heading into that event?"

xiv.

The university has long been obsessed with the metaphor of Jefferson's shadow. At the centennial celebration in 1921, the university mounted a pageant, in its new amphitheater, titled Shadow of the Builder. The script is not always subtle, as when Jefferson walks on to the amphitheater's stage for the first time:

A shadow falls upon them, the natural, morning shadow of Thomas Jefferson who has come silently up the steps at the end of the terrace. Jefferson is a tall, old man in an old-fashioned, snowy stock, and suit of homely gray broadcloth.

At one point the marquis de Lafayette, speaking before a crowd on the Lawn, makes reference to the university, which was still under construction in 1824. "Its white colonnades are yet empty of young life," he intones, "but a shadow falls along them daily. Athwart the centuries, so that your sons and their sons in turn shall walk within it, still will stretch the shadow of the friend of freedom, of truth, Thomas Jefferson."

As a third century begins, I think that more than ever the university is feeling uncomfortable in that shadow. The manly, martial patriotism on display at the hundred-year mark—the sheer confidence of it—no longer feels quite right.

When neo-Nazis marched on the Lawn last August, a small cadre of students and staff bravely defended the statue of Thomas Jefferson on the north side of the Rotunda. A few weeks later students covered that same statue with a black shroud, denouncing Jefferson as a white supremacist. A subsequent student council meeting erupted into shouts of anger as students debated demands made by the university's Black Student Alliance. Few people know about the "sex" scandal from 1954, but a since-discredited Rolling Stone article in 2014 about an alleged rape on Grounds brought to the surface many of the challenges and obstacles faced by women at the university—everything from harassment to horrific violence. More recent controversies have involved the role of big money at the university.

"One of the objects in my book is Philip Alexander Bruce's five volumes," I tell the reporter. "Nothing quite like it has been written since, largely because we've lost that confidence in what this place is—which isn't always such a bad thing, honestly. There is really remarkable history and commemoration being done by students and scholars right now—the President's Commission on Slavery and the University, the JUEL project, the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers. A book about slavery is in the works and another one about the founding. My thing is just a blip although perhaps it's not a coincidence that a bicentennial history in 100 objects is so modest, atomized even."

"People are skeptical of the grand narrative," the reporter says.

"They are," I say. "It's the age we live in."

"But it has something to do with UVA, too, don't you think?" the reporter counters.

And she's right. No institution excels at engaging with its worst history. And two hundred years is a lot to make sense of. The big histories will come again, I suppose, but for now, regardless of how the big-budget bicentennial pageant, set to begin at 7 p.m. on October 6, ends, I imagine it will feel different from how it did a hundred years ago:

Jefferson comes down the steps to the lawn, his shadow yet a moment lying in the last path of light.

Brendan Wolfe is editor of Encyclopedia Virginia, a project of Virginia Humanities. He is the author of "History Writ Aright," about the unveiling of the Robert E. Lee monument in Charlottesville.