MAYBE A MAP WOULD BE GOOD

Those maxed out on pre-war fever may have found their most eloquent spokesman in Neal Pollack, who wrote in Seattle’s The Stranger last week: “Shut up, anti-war people. Shut up, pro-war people. Shut down your computers and shut down your goddamn pieholes.” They also may have found their ideal book in Tony Horwitz’s 1991 travelogue, Baghdad Without a Map and Other Misadventures in Arabia, a volume as good-natured and readable as it is devoid of political posturing—or, for that matter, political context or even substantial insight.(1)

That’s the downside. The upside is that Horwitz is the tourist so many of us long to be: Armed with plane tickets to Yemen, Cairo, Baghdad, Tehran, Tripoli, Khartoum, Beirut and the West Bank, he’s unafraid to use them. Although perhaps he should be. In a chapter on flying in the Middle East, he tells the tale of an emergency landing, the cause of which was explained by a suddenly pale flight attendant: “The Sudanese forgot to give us gas.” Elsewhere, Horwitz is shelled, confronted by giant knives called jambiyas, given the hard sell by arms dealers and actually interrogated in that “bare room with a naked light bulb” you may have read about in any number of bad novels.

For the purposes of this feature,(2) his several trips to Iraq—all taken just prior to the Gulf War—are of especial interest. Horwitz confesses to nurturing romantic images of Baghdad. “The actual journey,” he recalls, “resembled walking through the gate of a maximum-security prison.” Imposing portraits of Saddam Hussein peer down from everywhere, like Big Brother. His government handler even wears a Saddam Hussein wristwatch: “‘Saddam is like Superman,’ the official said, showing how the watch hands ticked across the leader’s cheeks and brow.” When Horwitz attempts to strike up a conversation by asking about the weather, he is told that in Baghdad the weather is classified.

You can’t get more Orwellian than that, and Baghdad Without a Map is most interesting when it provides that street-level take on totalitarianism. In last week’s book, Iraq: In the Eye of the Storm, journalist Dilip Hiro erred by providing too little of this. Horwitz’s weakness is just the opposite: He falters when the circumstances demand a complex understanding of recent politics and history.

“I not understand you Americans,” Tariq, a young Iraqi street vendor tells Horwitz. “Born in the USA” is blaring from a nearby boom box. “You make good clothes and music. You have California girls. But you start this war on us to help Israel. Why you do this?”

Although Horwitz does not make this clear, Tariq is referring to the Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988), which was ending just about the time of Horwitz’s visit.

“I tried to explain that most Westerners believed that Iraq had started the war,” Horwitz writes. “Tariq looked at me blankly. Big Brother was watching from life-sized photos on two of the stall’s three walls.

“Tariq’s neighbor, who owned the boom box, wandered over and began jabbing his finger at me. ‘He says you can have your Bruce music, you can have it all back,’ Tariq translated. ‘Now that we win the war, we not need to beg America for anything anymore.’”

By referring to Big Brother, Horwitz suggests that Tariq was duped into thinking that America had anything to do with the start of the war. In Iraq, Hiro argues that, in fact, we encouraged Saddam to invade Iran. Regardless of whether that’s true, the United States provided Iraq decisive military and economic assistance. So where does anti-Americanism like this come from? And should you take it from a guy listening to the Boss?

Horwitz has no idea and, apparently, prefers not to speculate.

You might call Baghdad Without a Map Tony’s Excellent Adventure. But it pales beside Peter Maass’s 1996 account of the Bosnian War, Love Thy Neighbor. Although a journalist, Maass saw himself—by virtue of being an American and a human being—a participant in the events he covered. For that reason, he struggled with politics and conscience.

Horwitz’s world view can be summed up by a diplomat he meets in the Sudan: “‘Now that we’ve well and truly fucked the Third World,’ he said languorously sipping gin, ‘it is the white man’s burden to sit back and watch it fall apart.’”

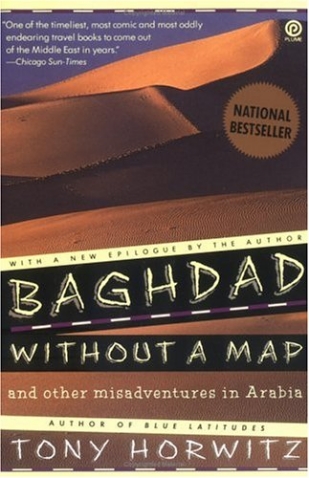

Baghdad Without a Map by Tony Horwitz (Plume, 285 pages)

Concord (NH) Monitor, March 2003

___________

1 I’m pretty hard on Horwitz in this review. I didn’t have space enough to make two things clear: 1) Baghdad Without a Map was a lot of fun to read; and 2) Horwitz went on to write Confederates in the Attic, a fabulous and insightful book about the impact the Civil War still has on present-day Southern culture. I used to be a reenactor, and I can say with some authority that he perfectly captures the absurdity of that particular hobby. And he writes about an incident near the Tennessee/Kentucky border in which the Confederate flag apparently provoked a murder. This one chapter has more compassion, insight and intelligence than all ofBaghdad Without a Map.

2 During the run-up to war, I was a copy editor at the Concord Monitor in Concord, New Hampshire. I also wrote reviews for and edited the paper’s Sunday Books section. I proposed to my editors that I feature weekly a review of an Iraq-related book. I was interested in boning up on the region (Okay, not boning up, starting from scratch), and I thought it might be cool for readers, too. My idea was met with deafening silence. So I just did it anyway. I only ended up reviewing a handful of books, though. It was too much effort, with no freelance help. And at that point, the choice of books to review was slim. My how that’s changed in the years since.