FREAKING OUT IN EARNEST

Far be it for any sufficiently humble reviewer to disagree with the New York Times Book Review, but here goes anyway: Jo Ann Beard’s essay “The Fourth State of Matter,” the one that first appeared two years ago in the New Yorker, again in the most recent volume of The Best American Essays and now finally in her collection, The Boys of My Youth, is not one of her weaker essays, or in any event, the least of the best. On the contrary, it remains a wonderfully crafted, engagingly voiced account of her own horrific sideswipe with death in November 1991, when a post-grad in the University of Iowa physics department, where Beard worked as an editor, brutally murdered a student, several professors and an administrator before killing himself.(1)

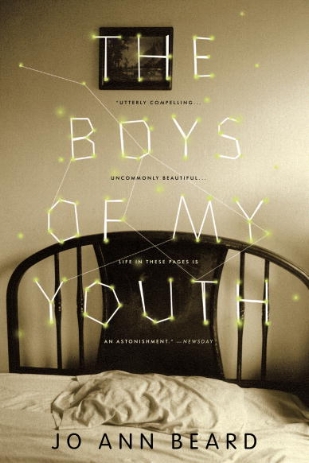

Beard, a Quad Cities native, is a recent graduate of the University of Iowa’s Program in Nonfiction Writing and a 1997 Whiting Foundation Award winner. Her collection of 12 autobiographical essays, The Boys of My Youth, was published by Little, Brown, in February. In it, she writes convincingly of her childhood, her close-knit female relationships and her father’s alcoholism, always in a voice that is sincere, funny and self-mocking.

Perhaps what has caused some critics to react defensively toward “The Fourth State of Matter” (and one New Yorker editor to dismiss it entirely[2]) is its narrative contention that other events in the author’s life, events that didn’t make the headlines or the evening news, should gain equal consideration when telling the story. After all, the shooter, Gang Lu, doesn’t make his appearance until halfway through the essay. Beard instead busies herself with telling readers about her dying collie, her “vanished husband” and a pack of unruly squirrels that has invaded her attic. Weaving these more personal anecdotes in with such a highly charged event as a multiple murder is risky, but what makes Beard’s writing compelling is also what opens it up to criticism: her refusal to see any event except in terms of her own life. Don’t expect to find any ink spilled over violence in America or even the agony of one community in the face of such a horrible crime. Antagonists of the personal essay will inevitably label this self-absorption, while champions of the form will more rightly counter that the best we can do as human beings is own up to our different points of view. Finding meaning in anything has to be accomplished individually and on our own terms.

“I have the distinct feeling there is something going on that I can either understand or not understand. There’s a choice to be made,” the author writes about the deaths of her colleagues. She ten tells her friend, “I don’t understand.”

Ironically, most of The Boys of My Youth is fairly indistinguishable from short fiction, except of course for its overlapping cast of characters. Beard’s writing throughout is stubbornly narrative, rarely if ever breaking into expository reflection, quite unlike the personal essay’s other heralded practitioners, Phillip Lopate and Scott Russell Sanders.(3) In essays like “Cousins,” the images—jumping fish, a floating baton—pile up beautifully, symbols of time passing or time refusing to pass: “… the fish is transformed. High above the water, it rises like a silver baton, presses itself against the blue August sky, and refuses to drop back down.”

The book constantly dwells on the issue of time, though it is written almost exclusively in the present tense. An essay like the title piece moves effortlessly between childhood and adulthood without any tense adjustment, contributing to an oddly effective voice that is neither entirely adult nor fully child. For instance, Beard describes herself dealing with the breakup of her marriage as “freaking out in earnest.”

The essay “Waiting” is one of the book’s most powerful. It opens as Beard and her sister Linda shop for a casket. The author does not reveal right away that the casket’s recipient, her mother, is not yet dead. Instead, she is waiting for them in her hospital bed. It is only two days before Christmas and the sisters have been bickering as they take shifts keeping watch over their mother, even counting down the days until, if the doctor is to be trusted, she will be dead. This essay—and so much of Beard’s writing—seems to be caught up in the guilt, dread, hope and pain of moments like this.

Without reading even a page, though, there is something remarkable about The Boys of My Youth. That it is a collection of autobiographical essays and not a more easily marketable memoir, novel or even collection of short stories represents no small risk on the part of the publisher and no small accomplishment for a relatively unknown writer like Beard. Consider the big bucks to be made and lost in the corporate world of publishing these days, consider how even a giant like Random House gets gobbled up by its German competitors, and the arrival of The Boys of My Youth might come to represent, for those of us bravely willing to risk hyperbole, something of a high-water mark in what is already being dubbed the golden age of the personal essay.

The Boys of My Youth by Jo Ann Beard (Little, Brown, 224 pages)

Icon (Iowa City), April 1998

___________

1 When Gang Lu committed his murders on November 1, 1991, I was a sophomore at the University of Iowa. It was Friday afternoon and snowing lightly. My friend Brad was giving me a ride from Iowa City up to Cedar Falls, where our girlfriends attended the University of Northern Iowa. I remember that we passed the physics building on our way out of town, at about the same time of the murders. Of course, we saw nothing and suspected nothing.

2 My reference here is to the longtime editor of the magazine’s “Talk of the Town” section, who visited the University of Iowa’s nonfiction writing program to talk about publishing in The New Yorker. His advice was to start small, by pitching him a Talk of the Town piece. He will not, however, deign to give you his phone number or e-mail address or fax number. So good luck.

Anyway, in the course of that talk he expressed disgust at the magazine’s new rubric, “Personal History,” and especially such writing appearing in the fiction issue. I can’t remember if he mentioned Beard by name, but her essay appeared under that rubric and in the fiction issue.

3 I don’t think I would, anymore, call Scott Russell Sanders “heralded.” I’m not even sure he’s particularly good. Phillip Lopate, yes.