'FARANG' SQUARE

Who reads a novel to be hectored? Especially a detective novel. There may be a masochistic few who actually enjoy being addressed as farang (Thai for “foreigner”) and then repeatedly lectured on the colossal failure that is Western civilization. But why take it from a $24 book when the rest of the world is happy to do it for free?

Bangkok police detective Sonchai Jitpleecheep, the narrator of John Burdett’s new novel Bangkok Tattoo, is fond of throwing spitballs disguised as cross-cultural insights. Sometimes they’re vague (the toilet is at the center of Western culture). Sometimes they’re obvious (Americans are too uptight about sex). And sometimes they’re just labored (Americans are imperialists bent on exploiting Thai women for sex when they’re actually the ones being exploited).

There are times when Jitpleecheep has interesting things to say. He is, after all, the multilingual son of an American G.I. and Thai prostitute. He is a devout Buddhist surrounded by the worldly corruption of Bangkok. With his mother and his Machiavellian boss, Colonel Vikorn, he runs a Viagra-fueled brothel called The Old Man’s Club. He enjoys, in his words, “full-blown copulation.” His male police partner aspires to be female.(1)

Jitpleecheep, in other words, can’t help but have interesting things to say. And Bangkok Tattoo, like its superior predecessor, Bangkok 8, features moments of humorous, almost off-handed irony and insight that make its otherwise lifeless mystery hum. In Bangkok 8, the secrets of East and West could be divined among the ring tones on a cell phone. In Tattoo, they are found at an outdoor food stall selling grasshoppers.

These occasional asides, along with Jitpleecheep’s mordant, cool-headed storytelling, are what make Burdett’s books decent summer reads. The action is often grisly—Tattoo begins with a dead American john, his penis severed, his back flayed—but the tone is light, the locale exotic, and the pace quick. Throw in some international intrigue in the form of CIA agents who comically jump to the conclusion that al-Qaeda is behind the murder, and you get something like Graham Greene, only without the gravitas.

The problem is that Burdett, a square-jawed world-traveler who currently lives in Hong Kong, always ruins the fun with too much grumbling about American foreign policy or Western closed-mindedness. Then there is the groan-inducing speechifying. “Because when we look into the eyes of your people we see something, call it what you like. Soul?” slurs a drunk spook to Jitpleecheep. “The human mind before fragmentation? Something sacred we farang habitually amputate like tonsils because we don’t understand its function?”

Oh, brother.

In the end, he bats the question back to Jitpleecheep. “Now tell me this, Detective. When you look into the eyes of farang, what do you see?”

This could be a great setup if Burdett had something to deliver. Americans abroad often do think this way. When faced with the imponderables of Asia, they fall back on the comfort of clichés and stereotypes. But then so does Burdett.

The two characters at the center of Tattoo’s mystery—the prostitute Chanya and her dead lover-slash-client, the mysterious Mitch Turner—flatten with each page. Burdett’s efforts only result in more groans:

“He was a farang, (Chanya) admitted, with that excitable farang psychology that just could not accept life as it came. Why was he like that? He obviously wanted to turn her into an American, colonize her, in other words, as if she were some backward country that needed development. It drove him crazy that she resisted his attempts at psychic invasion. Worse, there was no hiding the fact that she owned a better mind than his. Of course, she had hardly had any education, but she could read his oversimplified moods as if he were a picture book, while at the same time he seemed to understand nothing about her.”

Oh, brother.

It would be one thing to accept Chanya’s clichéd assessment of Mitch, but her clichéd assessment of herself is what ultimately and disappointingly kills Bangkok Tattoo.

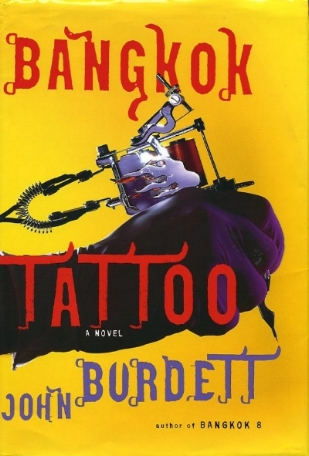

Bangkok Tattoo by John Burdett (Knopf, 320 pages)

Concord (NH) Monitor, July 2005

__________

1 Some interesting irony regarding critical reception to the book’s sexual themes. In the New York Times Book Review, Charles Taylor praises Burdett for being so enlightened as to not pity women stuck in a life of prostitution.

Burdett’s singular contribution to the contemporary mystery novel may be the way he breaks with the genre’s judgmental puritanism when it comes to the sex trade. Is it simply the adolescent strain in American hard-boiled fiction that makes it impossible for the genre’s practitioners to give us a stripper or prostitute who is aware of what she’s doing, who has chosen to do it and who is putting together a good life thanks to her profession? This novel’s explorations of the quid pro quo at work in the intersection of the Eastern sex trade and Western sex tourists doesn’t go as deep as the critically ridiculed examination of the same transactions in Michel Houellebecq’s “Platform.” But Burdett scorns the convenient fetish of victimhood so often present in writing about women like the ones who populate his book. The Westerners here don’t stand very tall. But at least Burdett has freed his Thai women from the condescending yoke of Western pity.

The irony is that just a few days earlier, Times op-ed columnist Nicholas Kristof was given the Michael Kelly Award for a series of columns that “focused attention on the continued sexual exploitation of young women in the brothels of Cambodia. With conviction, passion, and audacity, Kristof tugged at the world’s conscience, in the best tradition of Michael Kelly.”