BRINGING HIS SHITHEELS TO MAINE

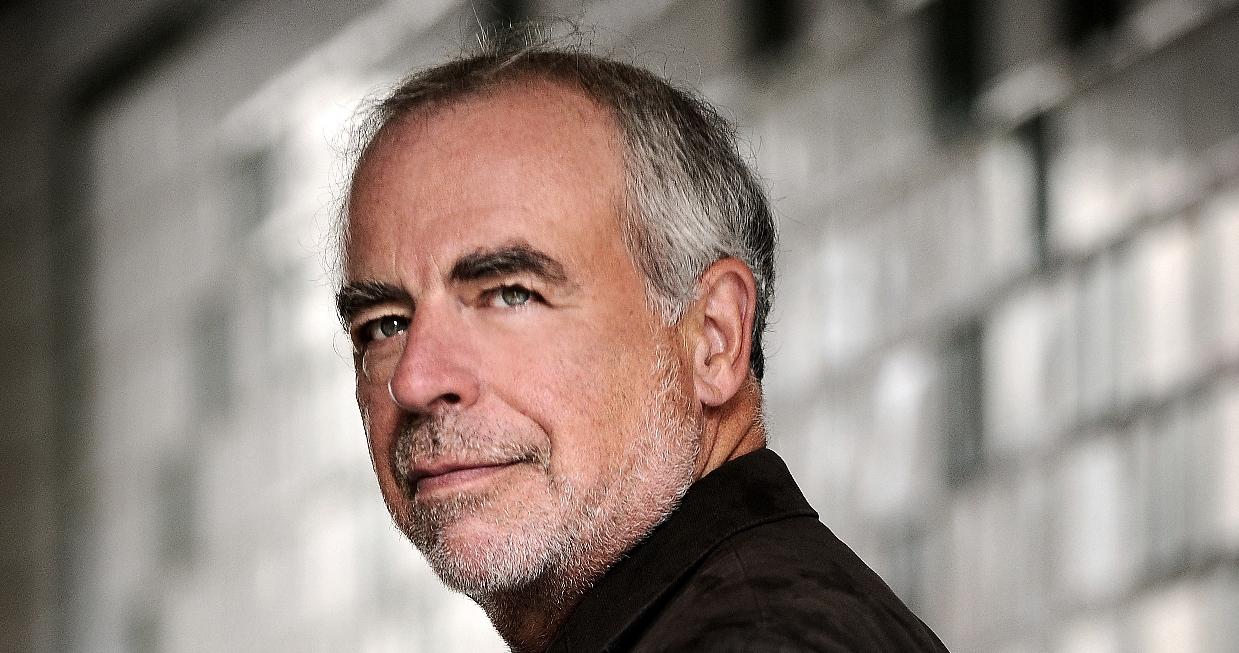

I ask Richard Russo—one outsider to another—if he considers himself a Maine writer. We’re sitting comfortably on his second-story veranda overlooking Camden’s main drag. It’s a sweaty Tuesday afternoon, but the tourists are noisy and legion, rumbling by on their search for the coast.

“Mainers, by and large, are very territorial,” the New York native begins cautiously, “and you felt that right away coming from outside. And I did, too. And yeah, I remember someone wrote some scathing piece about Cathie Pelletier, who’s a friend of mine and wrote half a dozen great novels about the County, but then she sinned. She moved away.”

Russo uncrosses his legs and takes a sip from his iced tea. “There are two things that you can do to alienate the territorial Maine writers,” he continues, this time a bit less cautiously. “You can leave, right, which is a sin. Or you can interlope. You can be a writer from somewhere else and then come in and write as if you’re a Mainer, when everyone knows full well that you are from away.”

Which, while not exactly answering my question, is true. Native Mainer Sanford Phippen has complained prominently, regularly and sometimes bitterly that Maine literature “suffers from a surfeit of superficial views from without.” In his essay, “Missing from the Books: My Maine,” he tells of his luckless search, within the pages of so much written about the state, for “the Maine I grew up in; the Maine I both love and hate; the Maine that is in my blood and ancestry and will haunt me always.” Instead, he claims to find too often the shufflin’ Downeast yokel, whom he calls “the Maine Native as Nigger.”

But for Phippen, what’s most important is not the divide between natives and Massholes but—and here one can imagine Carolyn Chute firing off a few rounds in agreement —between the rich and the poor. Or, more specifically, between those who can afford to leave and those who can’t. When dealing with folks from away, Phippen writes, there is always the hovering knowledge “that as a Maine person one may not have as much money or have traveled as widely.” And presumably that same self-consciousness can be turned on your native neighbors. In other words, you can write about Phippen’s “subterranean, unreported life”—as Pelletier did so wonderfully in The Funeral Makers 15 years ago—but you can’t leave. You can’t betray a Mainer’s “fierce pride.”

SANDY PHIPPEN'S MAIL

It’s a conflict that the interloper Richard Russo captures eloquently in his latest novel, the Maine-set Empire Falls, published in May by Knopf. Filled with equal parts heartache and belly laughs, the book’s home is the fictional ex-mill town of Empire Falls, and its centerpiece is a high school football game, which Russo’s hapless hero Miles Roby reluctantly attends with his friend Cindy Whiting. (Why reluctantly? It’s the proverbial long story, having to do with the fact that Miles, who runs the Empire Grill, is in the throes of a divorce—his wife Janine having fooled around with the health club guy and then confessed it to a senile priest who promptly blabbed the news around town—and that Cindy Whiting, altruistic and handicapped, has cultivated since childhood a stifling, thoroughly unrequited love for Miles. Oh yeah, and Cindy’s mother, the defunct mill’s owner who has an uncanny way of controlling everyone’s lives, is Miles’ boss.)

As Miles returns from a trip to the concession stand, he is confronted by Jimmy Minty, a policeman and Miles’ nemesis.

“How come you’re setting over here with the bad guys?” Jimmy wanted to know. He was in street clothes and he seemed eager to shake hands, though Miles held a Coke in each. “You ashamed of your own hometown?”

“We got here late,” Miles explained, sliding past both the policeman and Cindy, then staring at the same woman who hadn’t wanted to budge earlier until she finally moved down again. Fairhaven, he noticed, had added another field goal, making the score 17–zip. “That forced us to sit over here with the winners,” he added, just barely emphasizing the “i” in “sit.”

That tiny correction of Jimmy’s grammar opens up a floodgate of bad feelings that results short term in tears and Cindy Whiting almost being knocked off the stands, and long term in fisticuffs and incarceration. Such is the importance in a small town of who went to college and who didn’t; who left the state and who didn’t.

Later in the day, still burning, Jimmy tells Miles: “See, I cared who won that football game today. Maybe people like you think that makes me a nobody, but you know what? I don’t give a fuck. Mr. Empire Falls? That’s me. Last one to leave, turn out the lights, right? This town is me, and I’m it. I’m not one of those that left and then came back. I been here all long. Right here is where I been and it’s where I’ll be when the sun comes up tomorrow.”

Even though Miles is a native, Jimmy informs him that his neighbors nevertheless view him as an outsider. “You know what they see when they look at you?” he says. “That they ain’t good enough. They look at you and see everything they ever done wrong in their lives.”

It’s as if Richard Russo’s been reading Sandy Phippen’s mail.

Back in Camden, with the white patio furniture and the sweating iced tea, Russo points out: “This is a book in which people have dreams. Nobody in this book seems to be where they want to be … The character in the novel that at times I didn’t have a lot of sympathy for but who my heart broke for is Jimmy Minty. He’s very defensive for having stayed. He’s proud of going to the football games. He’s the one who loves this town, who has no ambivalent feelings at all. He is in many respects a shitheel, but my heart broke for him.” A fitting epigraph for so many of Russo’s characters.

FROM MOHAWK TO MISSISSIPPI

The irony is that, for all intents and purposes, Empire Falls could be the upstate New York town of Mohawk or any of the other fictional “away” locations that Russo has written about in such novels as The Risk Pool, Nobody’s Fool and Straight Man. I ask him if the settings are interchangeable.

“I think it probably is, if not exactly interchangeable—I mean, I write more about class than I do about place,” he says. “It’s funny, when you write about class, people always think you’re writing about place for some reason.” According to Russo, however, his Mohawk and North Bath and Railton, Pa., and Empire Falls, Maine, are the same, give or take the Bean boots. They are all populated by regular folk “who do blue-collar jobs and belong to a certain class in terms of what job they do and the amount of money they make and the amount of education they have. Those things are constant in all of the books.”

He leans forward. “And I often have people come up to me and say, ‘Boy, that town you wrote about—’ whether they’re talking about The Risk Pool or Nobody’s Fool, they say, ‘Boy, that town you wrote about, you just got it nailed. That is my hometown.’ And I’ll say, where you from? And they’ll say Mississippi.”

Russo’s face opens up in a big laugh.

Empire Falls is his fifth novel and its merits have been widely and justifiably noted. Sprawling, intimate and accessible, it fits snugly in the tradition of storytellers from Dickens to John Irving. Its laughs are many, but so are its insights into a cast of drifting and wise-cracking characters and the uncomfortable lives they find themselves leading. Russo claims the book’s write-up in the Los Angeles Times was “pretty close to a full body slam,” but in fact the reviewer’s quibbles were few (perhaps the symbolism—like a vertigo-stricken Miles attempting to paint the church steeple—could have been toned down, according to writer D. T. Max). Meanwhile, the New York Times’ A. O. Scott unabashedly declared, on the front page of the June 24 Book Review, that Russo is his hero.

It’s been a nice coming-out party for a guy who grew up in tiny Gloversville, N.Y., a town that itself sounds fictional. “It’s a little bit north of Albany,” Russo explains. “Used to be the glove capital of the United States, back when we still made things in America.”

Russo, the son of working-class parents, says his childhood was fine. “I loved it. But there was the sense for young people that you were gonna have to leave town in order to get a job. It had that in common with a lot of mill towns in Maine and New England and the rust belt of New York—great place to raise your kids, but once those kids get raised, they have to go away if they intend to find work.”

Russo went away to Arizona for graduate school and then taught creative writing at the University of Southern Illinois in Carbondale, where he began his novel-writing. A job at Colby College in Waterville offered him the opportunity to teach only part-time. “That’s what I wanted right then,” he remembers. “I think I had just finished Nobody’s Fool, and I was interested in devoting more time to writing.” Then, with Russo’s help on the script, Nobody’s Fool became a Hollywood film—in fact, that rarest kind of Hollywood film, a good one—starring Paul Newman, Bruce Willis, Melanie Griffith, and the late Jessica Tandy. His career taking off, Russo left Colby after five years and turned full-time to his scripts and novels. He also relocated, with his wife and two daughters, from Waterville to Camden.

He says the publication of Empire Falls has “blown his cover” in the resort town. “For the most part it’s great because everyone here has offered congratulations and well-wishes, and that’s very nice,” he acknowledges. “But it’s also not quite the same as being able to pass along anonymously, which I’ve always kind of enjoyed, too.”

THE ARTIFICIAL PEOPLE

In her essay “The Other Maine,” Carolyn Chute writes that she’s having a dream—no, a nightmare. “At first, in this dream we are all pretty much as we really are. I park outside the post office and grocery store where the people of my small Maine town nod hello or stop to gossip. I love my people here. They are visible people. When you look at the face of one of them passing you in the produce aisle, you know the history of that face—the gossip, the rumors, the truth. You see the complete person.” What destroys the dream, she says, are the “artificial people” of the state’s tourism commercials, the interlopers who are “untouchable, unknowable, artificial, dangerous.”

I trot out this passage for a couple of reasons. One, it’s an ironic twist on Russo’s—but to be fair, society’s—notion of celebrity and wealth as visibility, while the grunts of the world, like the blacks in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, toil in unseen and unknowable obscurity. Come on, though. Would a homeless man in tony Camden really be invisible, or is it more likely that he would provoke an ordinance aimed at cleaning up the riff-raff? Norman Mailer, only partly tongue-in-cheek, made the point over 40 years ago in response to Ellison’s novel: “Invisible Man insists on a thesis which could not be more absurd, for the Negro is the least invisible of all people in America.”

Two, it’s worth pointing out that Empire Falls’ working stiffs share something in common with Chute’s “real” Mainers: They are, to be sure, seen. But unlike their dreamland counterparts, they are struggling with all their wits to duck and hide—and not from outsiders, either. (Townsfolk regularly spread rumors about rich businessmen in their BMWs coming to buy the boarded-up mill. “The hordes of visitors who poured into Maine every summer were commonly referred to as Massholes,” Russo writes, “and yet when Empire Falls fantasized about deliverance, it invariably had Massachusetts plates.”) No, they’re hiding mostly from each other. Like so many small town novels, Empire Falls is driven by secrets: what people don’t know about each other and themselves, what they find out and wish they hadn’t.

By the end, some of the answers arrive in a jolting and all-too-familiar act of violence.

According to Russo: “This was a scary book from the start for me.” One of the reasons, he says, is because he was only learning about his characters, too. “When I wrote that final scene that has all the violence in it,” he confesses, “I did not know who was going to survive.”

HOW THE SILVER FOX HANGS

Russo admits to being interested in class issues; he admits to writing about them; but that doesn’t mean he’s particularly game to gab about it. “I find talking about [class] frustrating because it reduces human experience to ideology, which makes me very uncomfortable,” he says. “If I were that interested in ideology as opposed to human experience and what it feels like to live, then I would write nonfiction. I would write about ideas. I think of myself as writing about people and human experience in a way that ideas cannot be ignored. I mean, you can’t read Empire Falls without coming to some ideological conclusion. There’s politics in it. But I’m not interested in writing about politics.”

Nor is he particularly interested in talking about humor—undeniably the glue that holds his novels together, that charms readers and reviewers equally, and that makes his politics (best articulated as: “If anybody’s gonna get stiffed in America, it’ll be working class people almost uniformly.”) more palatable. “Humor is very hard to grasp,” he asserts. “It’s very hard to have a good discussion about what is funny. It’s funny if you laugh at it, and it’s not if you don’t.”

Which is fair enough. And it reminds me of B. R. Myers’ diatribe against literary prose in the current Atlantic Monthly. Picking on Don DeLillo in particular, he observes how reviewers have practically fallen over themselves guffawing. “At the same time,” Myers complains, “they refuse to furnish examples of what they find so amusing.” In the spirit of better criticism, then, I offer this passage, wherein Janine, Miles’ soon-to-be ex, argues with her soon-to-be husband Walt, a.k.a. the Silver Fox, who has been fibbing about his age.

“The problem is you lied to me, Walt,” Janine said, realizing that of course this too was a lie, and hating herself for it. That he had lied was the reason she should’ve been upset with him, but it wasn’t. The reason she was upset was that she’d been looking forward to at least twenty years’ worth of spirited, vigorous sex, having largely missed out on the last twenty by being married to Miles. But by the time she was sixty she’d be humping an octogenarian, or trying to. Discovering the Silver Fox’s correct age also explained why on a couple of recent occasions Walt—who for a small man was well hung, God love him—had required considerable manual assistance to get out of the gate. What if in a few short years all her well-hung man did was hang? Janine glanced over at her mother, to whom she hadn’t breathed a word of this because she knew how hard Bea would laugh. She was, after all, another tragic example of how much God seemed to enjoy frustrating the shit out of women.

I would only submit to Mr. Myers that not only does this passage rightfully earn a guffaw or two, but it also sets the reader up for that inevitable, Russo-ian moment when his heart must break for Janine. Myers, meanwhile, notes “how pathetically grateful readers can be when they discover—lo and behold!—that a ‘literary’ author is actually trying to entertain them for a change.”

“Well, I think there’s certainly some truth to that,” Russo responds. “I too have very little patience for any, quote, serious writer that does not take seriously his or her obligation to entertain. I can’t go there if they’re not going to entertain me. If I suspect that’s what’s going on, that this is going to be a weighty book, if I’m going to do all the heavy lifting and the author is not interested in making my load lighter, I’m going to go somewhere else.”

The trick to humor, instructs Russo, is to make it look effortless. And the wonderful reward, he adds, is that “it allows us into some fairly weighty places without ever feeling that weighty. The illusion holds if you’re lucky. And if you’re reasonably good at it, you can go to some places by means of humor that you would never want to go without it.”

Like Maine, perhaps? Russo isn’t saying. Suffice it to say that if Empire Falls isn’t precisely a Maine book—at least according to the standards set by Sandy Phippen and Carolyn Chute—then Maine, with all its quirky humor and its working class roots, is certainly a Russo kind of place. It’s a happy irony well worth savoring.

Empire Falls by Richard Russo (Knopf, 496 pages)

Maine Times, July 2001