BOUND FOR A CRASH

At least Frederick Turner knows what his problem is. In 1929, the first-time novelist has placed front and center a real-life character who barely registers as a character at all: the jazz cornetist Bix Beiderbecke.

Right there on page 3, an old friend of Bix wonders what it is about old photographs that fail to capture any consistent essence of the young genius, the soft-spoken white kid who helped mold jazz into high art and who died of gin and pneumonia at the age of 28. Yup, the hair is right, and those big ears are definitely his. But somehow the man is still missing. It’s “as if even in the random, improvised midst of his life Bix had wished to reserve some part or essence of himself from the pitiless inquisition of his peculiar, unpremeditated fame and the camera’s eye, managing in whatever circumstance that shy, long-lashed, down-looking attitude that precluded definitive image.”

Such a statement could be an ambitious writer’s self-dare or an early mea culpa. So which is it going to be? This is why we read on, happily encountering plenty of Tommy guns and hot solos, a few meditative interludes and some entertaining walk-ons by Al “Snorky” Capone and the French composer Maurice Ravel. 1929 is packed with pulp and artistry (both in subject and execution), but in the end it’s a game attempt that fails.

The bottom line is, if bummed-out and absent-minded Bix can’t perk up for Clara Bow (“Must be maybe a million guys don’t know me at all would like ta be where you’re at now,” the Hollywood It Girl whines), how can he be expected to carry 390 pages?

Part of the problem is that, in the hundred years since his birth, pop culture has flattened Bix’s story into a hoary Hollywood archetype. In fact, he was the archetype of the archetype. He was James Dean before James Dean. He was Kirk Douglas in 1950’s Young Man With a Horn, the naive and tortured musician trying to “hit a note that nobody’s ever heard before.” Clever and sexy enough to trade barbs with Lauren Bacall (“You can call me Amy.” “I bet I can.”), he was still too stupid not to destroy himself.

He was—and it almost hurts to type this—living fast and dying young.

Nor does it help, if you were hoping to traffic in something more valuable than Tinseltown clichés, that Bix was from the stix, or, put another way, Davenport, Iowa. It’s a place the biographies invariably describe as uptight and hopelessly German, one where, if mothers and musicians unions had anything to do with it, jazz would be left on the levee where it belongs. Now, if this reviewer sounds defensive, it’s because Davenport is his hometown, too, and when Turner goes so far as to imagine the high school’s bulking façade as a sort of penitentiary, it can’t help but sting. Perhaps the birthplace of an archetype must also be an archetype: the birthplace of alienation. All the more reason, then, to kick Bix free of this.

Turner’s ploy, and at first blush it’s a sound one, is to give us Bix through the cool and cynical eyes of Herman Weiss. When he first meets our much-worshipped hero, Herman only shrugs: “I figured you for the band. I don’t listen to music much.” A mechanic and booze-runner for Capone’s Windy City gang, the fictional Weiss is Nick Carraway to Bix’s Gatsby: an outsider who is wooed and then disillusioned. When the heat in Chicago turns up, he throws his lot in with Bix, working as the band’s road manager. He takes care of his slowly unraveling friend and plays housemother to a crowd of delinquent musicians until one of Bix’s drunken breakdowns drives him away. “It was too terrible to watch,” he confesses, not without some guilt.

Herman’s character (and that of his kid sister, Helen, who dangerously dumps a guy called Machine Gun Jack for Bix) offers Turner a welcome excuse to write one long, hissing sentence after another about life in the mob:

(Herman) remembers one morning in particular after a long night, when he found himself under the hood of the Big Shot’s Caddie, a maroon seven-ton tank with steel chassis and bulletproof windows, his eyes like cinders in his head, his whole body numb with fatigue: installing a new carburetor and set of plugs and adjusting the idle while Machine Gun Jack McGurn breathed down his neck, telling him every few minutes how the Boss needed his rig at a quarter-to-noon sharp, and with every clipped reminder his fingers got slower and thicker while his eyes sizzled and blurred, and he was just pulling back from under the long gleam of the hood and wiping those fingers on a rag while the Caddie purred like a pussy when here came a clatter of footsteps down the rampway beneath the Metropole, and it was the Big Shot himself—Capone—swaggering surrounded by bodyguards …

One wonders, a little indulgently, if the book couldn’t go on like that forever, Turner getting his DeLillo on, Herman hanging out with the wiseguys. When Bix worries over his piano compositions or wonders about his future as an artiste, the prose can’t help but sag. And when Herman disappears back into the underworld midway through, our mediator to the mysteries of a ticking genius is gone with him.

He turns up again an old man, living across the river from Davenport, still chewing on the questions of Bix’s demise and his own departure. How had he known he must get “out of the wreckage of a life, forever”? Perhaps there’s no answer to that, he decides. But then why, “after all these years, were these crowds of latecomers milling around Davenport and trampling the grasses of the grave when all they had to base their adulation on were a few old recordings?”

Only cranky old Herman would chalk up the legacy of Bix Beiderbecke that way, which is what makes him so endearing. He might have had the shoulders for a hefty novel like this one—so many words, so little plot—but, alas, Turner never gives him the chance. In the droopy, inarticulate care of Bix, on the other hand, 1929 is bound for a crash.

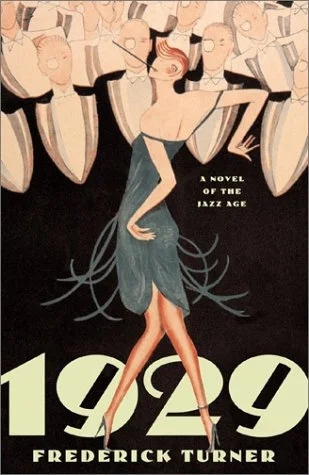

1929 by Frederick Turner (Counterpoint, 390 pages)

Concord (NH) Monitor, June 200