ALL WET

As novels go, The Gangster We Are All Looking For—Le Thi Diem Thuy’s beautifully told account of a Vietnamese immigrant family—is soaking wet.

The sea is a constant, foreboding presence. Bodies are washing ashore on the first page and they are washing ashore on the last page. A man tells his beloved that if she would marry him, “he would pull the moon out of the sky and turn it into a pool for her to wash her feet in.” “Bad water” is blamed for the death of a young boy, and a simple glass from the tap is drunk “desperately, as though it were a reprieve.”

Such pervasive dampness is hardly an uncommon phenomenon in the literary fiction of Vietnam, which is a coastal nation, after all. One practically requires a raincoat to peruse the work of Duong Thu Huong, the Communist state’s leading writer-dissident and water-conjurer. In Memories of a Pure Spring (2000), where all epiphanies come equipped with monsoons, the hero searches for freedom in “the sea of the sea,” only to end up drenched in a storm: “Rain, still rain. Water and more water, white sheets of it, as far as the eye could see.”

The Gangster We Are All Looking For goes a step further, telling us right at the start that in Vietnamese, “the word for water and the word for a nation, a country, and a homeland are one and the same: nu’o’c.”

The irony is that this novel, Thuy Le’s first, is not actually Vietnamese but American, retelling the oldest of American stories: that of immigrants desperately seeking assimilation. It features a dysfunctional family worthy of a Todd Solondz film, where the parents scream and fight (“like two dogs chasing each other’s tails”), the mother chops off her hair in a fit, and the daughter runs away to become a writer.

In Confucian Vietnam, the family is the gravity that keeps one anchored to the earth. In a California housing development called Linda Vista, on the other hand, a family portrait is secreted away up to the attic and left behind in the next move. A ringing phone is met with terror for the obligations that may wait on the other end.

Still, as this family stumbles through its stormy version of the American Dream, where everyone is an outsider trying to fit in, Vietnam lingers close by. It’s a connection not so much of blood, the narrator is fond of saying, as of water.

That narrator is the family’s young daughter, and while point of view is slippery here, the bulk of the book is presented through her eyes and ears. There’s not much plot to speak of; think of this slim novel as a collection of images that gathers the rolling force of a long poem. The narrator is forever seeing the world as magical and sad: A butterfly encased in glass “pressed down on the paper the same way my Ba’s heavy head pressed down on the pillow at night, full of thoughts that dragged him into nightmares when all he wanted was a dream as sweet and happy as the taste of jackfruit ice cream.”

She inherits this worldview from her mother: “Ma says war is a bird with a broken wing flying over the countryside, trailing blood and burying crops in sorrow.”

And her father, who tells her: “My family’s a garden full of dreamers lying on their backs, staring at the sky, drunk and choking on their dreams.”

It is this father, the title’s gangster, who is the brooding heartbeat of the book. His past is full of rumor and innuendo—maybe he was a gunrunner or a drug-dealer or a soldier. Whatever the case, he survives a Communist re-education camp, survives the boat trip to America, and survives America—for a while anyway. It’s a small kind of dignity: “His friends fell around him, first during the war and then after the war, but somehow he alone managed to crawl here, on his hands and knees, to this life.”

Credit Thuy Le, who lives in western Massachusetts, that for all the writerly self-consciousness her prose periodically succumbs to, readers can be left with a character as memorably haunting as Ba. By novel’s end, waterlogged and image-soaked, you won’t have found him. But it will hardly have mattered.

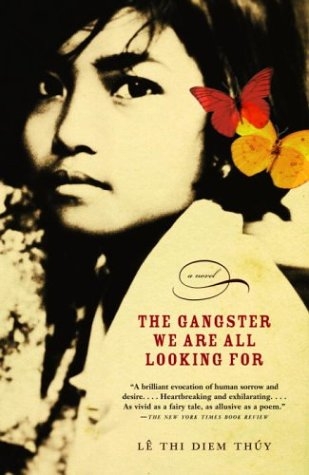

The Gangster We Are All Looking For by Le Thi Diem Thuy (Knopf, 160 pages)

Concord (NH) Monitor, July 2003